Raise your next round effortlessly

Raise your next round effortlessly

We help founders of seed, series A and B stage startups close venture capital rounds effectively

We help founders of seed, series A and B stage startups close venture capital rounds effectively

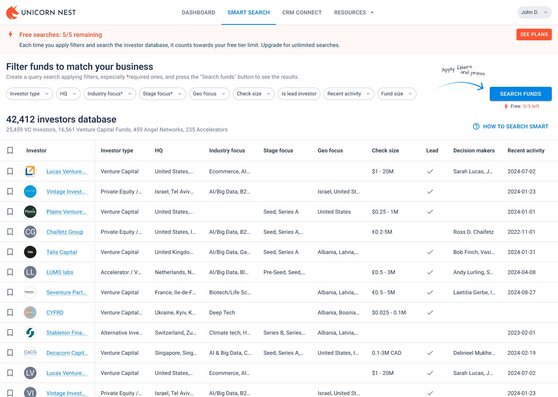

Biggest Database of Venture Capital Investors

42,412 investors

Collected and monitored since 2000

51,253+ key persons

Updated every two months

226,000+ VC Deals

Updated on a bi-weekly basis

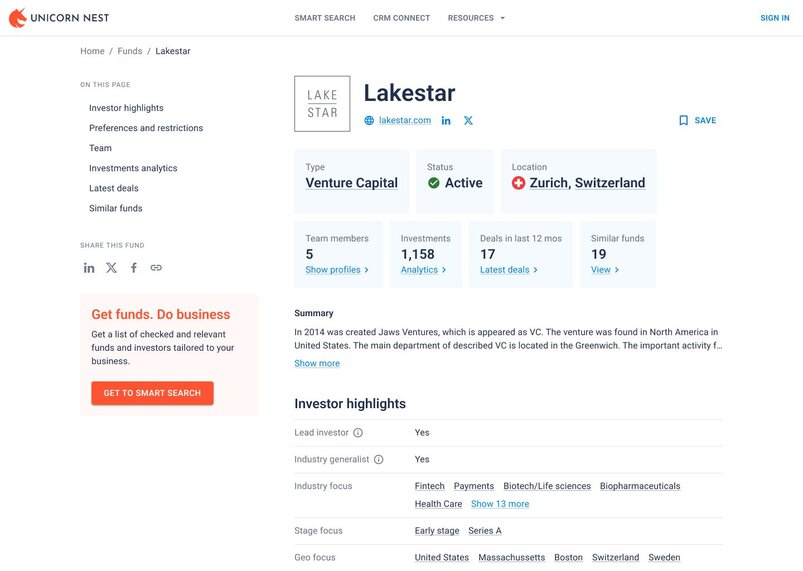

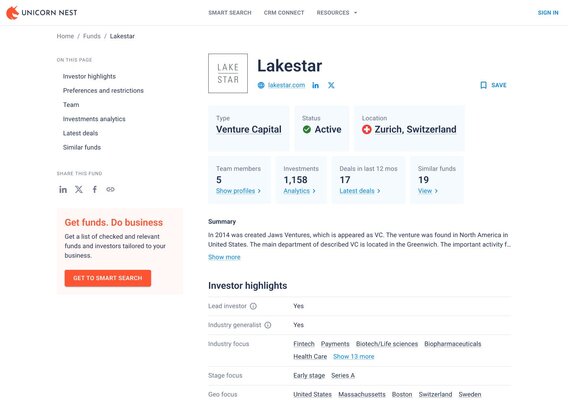

Get advanced analytics about investors, their strategy and investments

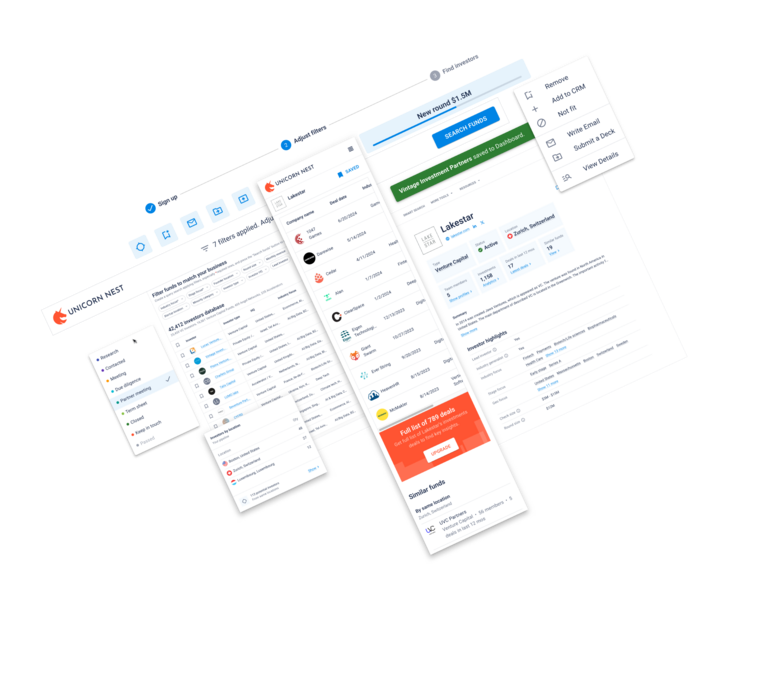

What You Can Do With Us

Find venture capital investors matching your startup profile

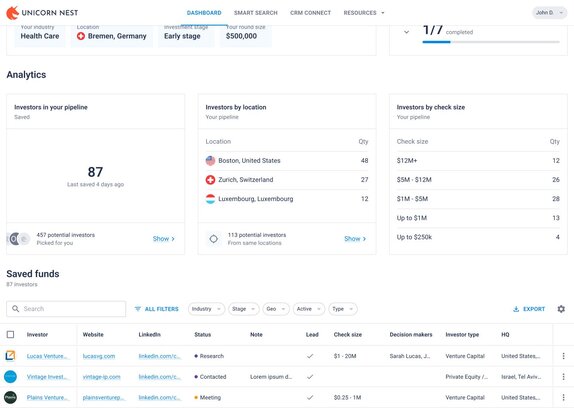

Track your fundraising progress and manage investor relationships

Get advanced analytics about investors, their strategy and investments

How We Collect Our Data

- Automated AI-enhanced data collection. We fully use the potential of LLMs to collect the recent data about venture capital investors, partners and venture deals.

- Manual Verification. Our team of 10+ analysts uses a set of our own proprietary tools for data cleaning and analysis, ensuring high verification standards.

- Press and Media Monitoring. To enhance our venture capital database, we cross-check our information with the help of news providers and venture capital data aggregators.

- Social Networks Monitoring. We regularly monitor top two social networks for VC, LinkedIn and X.com to ensure that we keep track of recent developments.

Trusted by 5000+ founders

Founder Reviews

"I am delighted to share our positive experience collaborating with Unicorn Nest in facilitating investment rounds for DreamTeam Project with one of the prominent European investment fund - Mangrove. Through our partnership, Unicorn Nest demonstrated exceptional expertise in managing the investment process. A late seed series deal worth $5 million was closed."

Oleksandr Kokhanovskyy, Founder @DreamTeam

"The Unicorn Nest team played one of the key roles in raising early-stage funding and is still supporting us in raising the next rounds with introductions and advice. The Unicorn Nest team is proficient in investment management and excels in understanding the unique needs of tech startups.”

Andrii Bezverkhyi, CEO @SOC Prime

"Unicorn Nest's team possesses a profound understanding of the tech sector's intricacies, making them an invaluable partner in navigating investment rounds. Their strategic approach to connecting startups with the right investors is both efficient and effective, ensuring that both parties achieve their desired outcomes."

Aleksandr Volodarsky, CEO @LEMON.IO

Used by Founders From

Frequently asked questions

What is Unicorn Nest?

We’re a team of fundraising experts with over 15 years of experience, helping hundreds of startups raise millions from investors across the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Our specialty lies in deep research and quality data, making us a trusted partner for your fundraising journey.

How does Unicorn Nest work?

We support startups at every stage of fundraising. First, we help you craft a standout pitch, then we connect you with the right investors. Need help with emails or financial models? We’ve got you covered. Plus, if you’re into cold outreach, you can use our automated platform to streamline the process.

What sets Unicorn Nest apart from competitors?

We’ve built our own unique, proprietary investor database using automated tools. Our goal is to become the largest verified investor database online, offering both a high number of investors and rich, detailed data to help you find the perfect match.

What’s the difference between Free and Paid Unicorn Nest Plans?

With Paid plans, you get access to more in-depth data, including detailed analytics, partner information, and contact details. You can also run up to 20 smart searches per month to fine-tune your investor search. Plus, you’ll have more flexibility with exporting and importing investor data for easier management.

How will I be billed for access to Unicorn Nest services?

We offer annual, quarterly, and monthly subscription options. Annual plans are billed upfront, quarterly plans are charged every three months, and monthly plans are billed each month.

How long will it take to secure the funding I need?

Fundraising timelines vary based on your experience, team, industry, stage, geography, and more. We suggest starting your campaign 4-6 months before you expect to close your round, to give yourself the best chance of success.